What strange subterranean passages of sentiment and tone, from the lively airs of the opera-bouffe to the plaintive entreaties directed toward deserted windows!

“Signori, something for charity`s sake! Take compassion on a poor unfortunate!”

And what an extraordinary and incredible mutilation and confusion of musical motives and words which give the impression of the bewildering song of a dreamer or the delirium of a musical maniac!

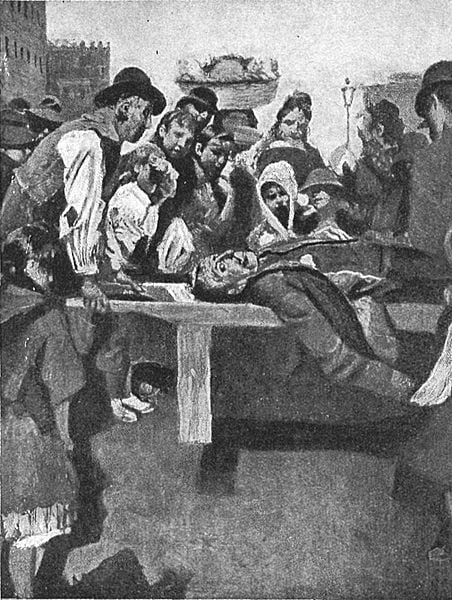

There came often a whole family, father, mother, and a nestful of children, who stood in a group in the center of the court and sang all together with wide-open mouths, each one on his own account, like a shipwrecked family on a raft calling desperately for succor to a far-off vessel.

Perfectly motionless

I remember also a diminutive hunchback who used to play upon a trombone larger than himself, out of which, with closed eyes, he blew distressing and threatening notes having no connection at all with one another. When he had finished he would remain for a time perfectly motionless, neither looking about nor asking alms, as though he feared to lower his dignity, and if he received nothing he would go away, head erect, wrapped in a superb silence.

And what impressed me deeply was an old man with a battered high hat, his long white hair falling over his shoulders, who, following a tune of his own, with an energy and seriousness worthy of inspiration, wbuld pound together two bent and weather-beaten cymbals, producing a noise resembling the successive breaking of window-panes. Every time his image comes to my mind I hear again the saddening clatter of his dilapidated cymbals as he dragged himself down the road, shaking his head mournfully, the prey of disappointments and troubles.

Oh, unfortunate music, what martyrdom is yours! Your divine art turned adrift never seems so desolate as when at certain hours of the day it makes its appeal to busy households where there is no spare time even for compassion. While you play and sing the cobbler hammers his last, the smith his anvil, and all hurry hither and thither without lowering a voice. Carts enter and depart and your tones are drowned by the cries of itinerant vendors of vegetables and brooms. Your verses of romance, of love, of the moon, and of paradise ascend in a vapor of soapsuds and mingle with the clatter of dishes, the bawling of children, the scolding of housewives, and the prosaic worries of every-day life.

Read More about The Lighthouse Keeper of Aspinwall part 12