Ancient Rome

It is a commonplace of literary history that Roman art was largely imitated or derived from the Greek, and in particular that Roman literature contributed little to the world`s store of masterpieces. Yet among the Romans the short story was esteemed more highly and was often more skillfully developed than it was among the Greeks.

The first of the stories chosen is from the historian Livy. Before his day there is very little material from which to select, although if the earlier writers of epic and history were better known to us, we might have found stories in the works of Livius Andronicus, Ennius, and the historians, most of whose writings have been lost. In the Letters of Cicero are numerous incidents falling within our category, but none of them of sufficient intrinsic interest to warrant their inclusion in this volume. Livy`s History abounds in episodes, many of them related with a certain matter-of-factness that characterizes a great deal of Latin prose writing. Still, Horatius at the Bridge is a stirring tale rendered doubly effective by its simplicity.

Ovid was a born teller of stories, and though he borrowed largely from the Greeks and was a fastidious poet intent upon achieving a refined and elegant style, the numerous myths which he treats at length in his Metamorphoses include half a dozen of the loveliest stories ever written.

Other poets and historians and miscellaneous writers—Valerius Maximus, Varro, Statius, Tacitus and Suetonius—tried their hand at story-telling, and even Vergil in his JEneid recounted episodes that are genuine stories, but none of them could rival the technical skill with which the minor poet Phaedrus turned the ffssopian fables and everyday incidents of life and history into graceful and appealing tales. Like the earlier fabulists, Phaedrus preached litde sermons. The most interesting parts of his work are the little anecdotes, like the one included in this volume; these are miniature stories. The other famous Roman fabulist was Avianus who, rediscovered in the Middle Ages, exerted a profound and lasting influence in France and Germany. But his work is neither so finished nor so attractive as that of Phaedrus.

Many genuine stories are found in the personal correspondence of the time, chiefly among the published collections of Cicero and Pliny the Younger. Pliny wrote several short stories which he elaborated with conscious skill, for he wrote with a view to publication. Throughout all modern literature we find stories, indeed lengthy stories (see Richardson), related through the medium of letters. This is a deliberate device employed to lend to the narrative an air of actuality. It would be enlightening to know whether Pliny wrote his Haunted House as a literary experiment, or whether he really believed the story. But supposing he related it as a fact—supposing even that all the facts were to be proved scientifically correct, would it be any the less a good story?

Matron of Ephesus

Petronius belonged to a different world in which Latin prose had lost a good deal of its rigid dignity, and like the literature of the late Hellenistic period in Greece, was characterized by a facile cynicism on the part of the writers, and an over-luxuriance of style. The writers were very numerous, poets, historians, satirists, and even scientists interspersing their writings with tales of haunted houses, ghosts, and all the supernatural apparitions that are the stock-in-trade of the story- writer. Petronius and Apuleius, however, stood head and shoulders above the rest of their contemporaries and followers. The Matron of Ephesus, hackneyed though its theme may be, is a masterpiece of satirical fiction, while The Dream is one of a dozen tales of mystery and imagination which constitute the chief glory of The Golden Ass. That rambling romance, it will be remembered, also contains the enchanting Cupid and Psyche, which is far too long for inclusion in a collection of this sort.

Just at what point Roman literature ended is a matter to be determined by the historians, but after the Fifth Century A.D. it becomes increasingly difficult to designate any tale as unmistakably Roman.

Then foreigners began to change the face of the Empire, Christianity damped the ardour of the artist and stifled the imagination of the storyteller. It is not until the dawn of modern times, some six or seven centuries afterward, when the fragments of Roman stories were again taken up and imbedded in the curious mediaeval mosaics of the Gesta Romanorum and the Hundred Ancient Tales, that we realize that the art of tale-telling had never been forgotten.

Throughout the break-up of Rome and the barbarian invasions, through the darkest years of the Tenth Century, the Latin traditions were preserved in the manuscripts of the monasteries, and on the lips of singers, minstrels, acrobats, and actors.

With Apuleius and Petronius the short story, as a literary-form, achieved a decided technical advance over the efforts of the Greeks. With these later writers the story was told largely for its own sake, and not to illustrate a moral truth or glorify the deeds of the Roman people.

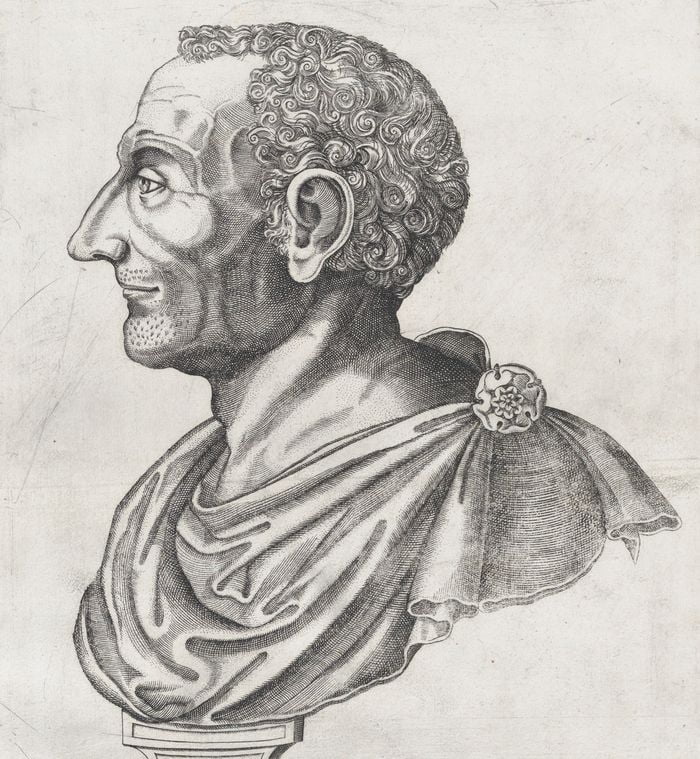

Livy (59 B.C.-I7 A.D.)

Titus Livius, known to us under the English title of Livy, though born in the provinces at Padua, spent most of his life at the capital, where he was a teacher and writer of history. His History of Rome was a monumental work, of which only a part has come down to us. Like practically all the historians of antiquity (and most of the modems, for that matter) he introduces stories and anecdotes on hearsay evidence, using them in order to glorify his country or to drive home a lesson. Horatius at the Bridge is a case in question, and though it may be founded on fact, it is probably apocryphal in detail.

The present translation (including Chapters IX and X of Book II) is a revision of that made by D. Spillan, published in the Bohn edition in 1872. There is no title in the original.

Horatius at the Bridge

By this time the Tarquins had fled to Lars Porsena, king of Clu- sium. There, with advice and entreaties, they besought him not to suffer them, who were descended from the Etrurians and of the same blood and name, to live in exile and poverty; and advised him not to let this practice of expelling kings to pass unpunished. Liberty, they declared, had charms enough in itself; and unless kings defended their crowns with as much vigor as the people pursued their liberty, the highest must be reduced to a level with the lowest; there would be nothing exalted, nothing distinguished above the rest; hence there must be an end of regal government, the most beautiful institution both among gods and men. Porsena, thinking it would be an honor to the Tuscans that there should be a king at Rome, especially one of the Etrurian nation, marched towards Rome with an army.

Never before had such terror seized the Senate, so powerful was the state of Clusium at the time, and so great the renown of Porsena. Nor did they only dread their enemies, but even their own citizens, lest the common people, through excess of fear should, by receiving the Tarquins into the city, accept peace even though purchased with slavery. Many concessions were therefore granted to the people by the Senate during that period. Their attention, in the first place, was directed to the markets, and persons were sent, some to the Volscians, others to Cumae, to buy up corn. The privilege of selling salt, because it was farmed at a high rate, was also taken into the hands of the government, and withdrawn from private individuals; and the people were freed from port-duties and taxes, in order that the rich, who could bear the burden, should contribute; the’poor paid tax enough if they educated their children. This indulgent care of the fathers accordingly kept the whole state in such concord amid the subsequent severities of the siege and famine, that the highest as well as the lowest abhorred the name of king; nor was any individual afterwards so popular by intri

guing practices as the whole Senate was by their excellent government.

Some parts of the city seemed secured by the walls, others by the River Tiber. The Sublician Bridge wellnigh afforded a passage to the enemy, had there not been one man, Horatius Codes (fortunately Rome had on that day such a defender) who, happening to be posted on guard at the bridge, when he saw the Janiculum taken by a sudden assault and the enemy pouring down thence at full speed, and that his own party, in terror and confusion, were abandoning their arms and ranks, laying hold of them one by one, standing in their way and appealing to the faith of gods and men, he declared that their flight would avail them nothing if they deserted their post; if they passed the bridge, there would soon be more of the enemy in the Palatium and Capitol than in the Janiculum.

First entrance of the bridge

For that reason he charged them to demolish the bridge, by sword, by fire, or by any means whatever; declaring that he would stand the shock of the enemy as far as could be done by one man. He then advanced to the first entrance of the bridge, and being easily distinguished among those who showed their backs in retreating, faced about to engage the foe hand to hand, and by his surprising bravery he terrified the enemy. Two indeed remained with him from a sense of shame: Sp. Lartius and T. Herminius, men eminent for their birth, and renowned for their gallant exploits. With them he for a short time stood the first storm of the danger, and the severest brunt of the battle. But as they who demolished the bridge called upon them to retire, he obliged them also to withdraw to a place of safety on a small portion of the bridge that was still left.

Then casting his stern eyes toward the officers of the Etrurians in a threatening manner, he now challenged them singly, and then reproached them, slaves of haughty tyrants who, regardless of their own freedom, came to oppress the liberty of others. They hesitated for a time, looking round one at the other, to begin the fight; shame then put the army in motion, and a shout being raised, they hurled weapons from all sides at their single adversary; and when they all stuck in his upraised shield, and he with no less obstinacy kept possession of the bridge, they endeavored to thrust him down from it by one push, when the crash of the falling bridge was heard, and at the same time a shout of the Romans raised for joy at having completed their purpose, checked their ardor with sudden panic. Then said Codes:

“Holy Father Tiber, I pray thee, receive these arms, and this thy soldier, in thy propitious stream.” Armed as he was, he leaped into the Tiber, and amid showers of darts, swam across safe to his party, having dared an act which is likely to obtain with posterity more fame than credit. The state was grateful for such valor; a statue was erected to him in thecomitium, and as much land given to him as he could plow in one day. The zeal of private individuals was also conspicuous among his public honors. For amid the great scarcity, each contributed something, according to his supply depriving himself of his own support.

Read More about Mendicant Melody part 1